Anastasiya Kazakova, Public Affairs Manager

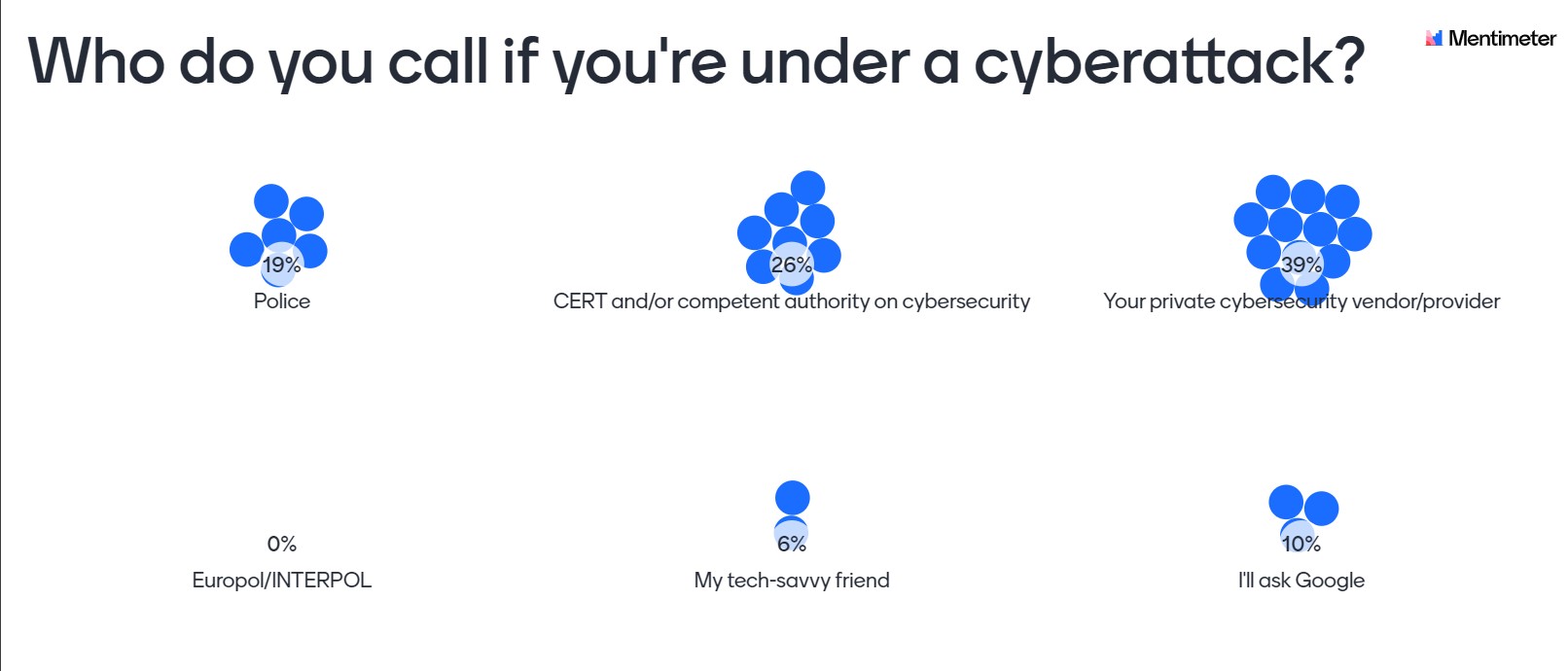

Who do you call if you’re under a cyberattack?

We organized Community Talk #2 and asked guests to share their answer: 39% said that their private cybersecurity vendor/provider would be the first on the list; CERT and/or a competent authority on cybersecurity comes second (26%); and police comes third (19%). The results you can see below:

But that’s not all. We had the second edition of our Community Talks on Cyber Diplomacy – no ties, no overly-formal discussions – to hear what cyber diplomats, cybersecurity researchers, academia, policy experts and law enforcement professionals fighting cyber threats also think. This time we had the honor of discussing this topic in greater detail with:

- Ambassador Nadine Olivieri Lozano, Head of International Security Division, Federal Department of Foreign Affairs, Switzerland (@SecurityPolCH);

- Neil Walsh, Chief of Cybercrime, Anti-Money Laundering and Counter Financing of Terrorism Department, UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (@NeilWalsh_UN);

- Ivan Kwiatkowski, Senior Security Researcher, the Global Research and Analysis Team (GReAT), Kaspersky (@JusticeRage); and

- Stefan Soesanto, Senior Cyber Defense Researcher, CSS/ETH Zurich (@iiyonite @CSS_Zurich) as discussant – a special role to challenge the discussion of the three panelists and provide a third-party opinion from a researcher policy perspective.

We focused on discussing existing and possible cooperative mechanisms in case of a cyber emergency and cyber incident and, particularly, on the implementation of the existing norms on critical infrastructure protection and assistance[1].

For every Community Talk we discuss three simple questions, and for Community Talk #2 they were as follows:

- what best practices already exist (and how far we as the global community went in implementing voluntary 2015 UN GGE norms G and H);

- what didn’t and doesn’t work to implement those norms and create effective global response frameworks; and

- what the priorities are for the global community in 2021 in this regard.

Starting with the positive reflections (recalling the existing good practices), Neil stressed the global community has norms, but they are beneficial only when they are actually operationalized and used. For implementing norms G and H, one of the first steps should be exploring cross-government culture as well as looking more into what capabilities we see that states have more and more advanced offense and defense cyber capabilities. Neil also mentioned that we have to build a government-based response, and within countries we should use all capabilities to try to understand the threat we are facing; otherwise discussing how a response should look without understanding the threat gets us merely into a philosophical debate. Overall, if we understand the threat, then we will be able to understand the areas of consensus among actors, and only then will we be able to move the discussion forward.

From a cybersecurity research perspective, Ivan said that many good practices for protecting CI already exist. They are: (1) making sure that systems are updated in a timely fashion; (2) deploying endpoint protection on the machines; (3) having offline back-ups of critical data; and (4) investing in human resources capable of detecting and reacting to anomalies inside the internal network. Speaking of global cooperative mechanisms – we fortunately have ways to cooperate more actively with CERTs, INTERPOL, Europol, and national cybersecurity agencies; however, there are no truly structured means for more operational cooperation and global responses in case of a cyber emergency affecting several countries and CI. Ivan added that he wished the norms were more detailed for more effective action. At the same time, we see at least private companies are more directly involved in global cyber processes cooperating with the public sector, and he expects to see increased threat intelligence sharing, transparent incident response processes and customer identification programs.

Finally from a cyber diplomacy angle we learned from Ambassador Olivieri that the matter of national CI protection (CIP), which is discussed within the UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG), is a complex question as different countries have different views on it. What’s more, CIP is a matter of national prerogatives and responsibility. In Switzerland, the Reporting and Analysis Centre for Information Assurance (MELANI), together with the national Computer Emergency Response Team (GovCERT), are tasked to protect CI by also participating in national and international info-sharing foras.

Nadine also added that the good practice for all states would be ensuring a trusted and efficient flow of information between operators of CI and relevant government actors as ICT threats are dynamic and volatile and need to be addressed in a swift and targetable fashion. With regard to the implementation of norms G and H, we have a mixed picture: as a takeaway from the current UN processes, states are at very different stages. Some have come a long way and have developed internal procedures, and some are just beginning to identify what CI is and develop processes to protect them. Many states are in-between these two extremes, but at the OEWG there are some national degelations that they did not even know those norms had existed before. So what we need is to raise awareness, help countries that are lagging behind, and give guidance on norm implementation in the format of capacity building, inter-state consultations, and multi-stakeholder dialogues. Nadine agreed with Ivan that norms are not detailed enough, and that’s why what is needed is to work on further implementation guidance rather than creation of new norms.

Where are we failing: what didn’t and doesn’t work to implement those norms and create global response frameworks?

Neil started and said we currently face the ‘policy vs. reality’ dilemma: we’re hearing from someone like Ivan working in the tech industry that we don’t really have specific language in norms, whereas it takes months and years of discussion for diplomats to agree on the language for norms because there are always strong political disagreements among states. Sharing from personal professional experience, Neil said that states face the same threats and the same cyber risks, and when Neil and his team, which is located on six continents, speak to states, all agree that we need to build cyber capacities; however, there are many factors – regional, political, legal, etc. – that influence this. We need a private sector whose role is to advise and guide these critical discussions. Yes, it is the decision to be made by states to allow the private sector to be in a room or not, but the risk we all face right now is while decision-makers discuss policies, and the private sector takes proactive steps already – this leads us to a discrepancy and moves us further from the reality, and therefore limits our capabilities to address the threats.

Ivan, sharing the cybersecurity research perspective, agreed with Neil about the gap between intent and implementation, but also mentioned that the norms are only a first step in the right direction, while there are still a number of issues that need to be addressed in the interest of global cyber-stability; namely: (i) acceptable use and regulation of dual-use software, such as commercial Trojans and zero-day exploits; (ii) more transparency regarding the alleged stockpiling practices of software vulnerabilities of national security services; and (iii) the lack of a common framework (or at least shared practices) to attribute cyberattacks. Ivan also stressed that while countries share more policies about their cyber engagements, there is, however, no information on how they would react to attacks. In the interest of deterrence, it would make sense to clarify the precise consequences for cyberattacks wherever possible.

Nadine supported both points on the ‘policy vs. reality’ gap and Ivan’s statements on the deterrence and attribution, but also added that when it comes to detailed discussions on CIP – it becomes a very sensitive issue. While the collaboration works quite well between technical specialists and CERTs, the discussions get tricky at the political level as it is becomes difficult to find the right words that everyone would agree to. However, what all states agree within the GGE and OEWG is that capacity building is crucial, as is building global expertise to have stable structures and frameworks to deal with ICT threats.

Nadine also shared that governments tend to work in silos and there are many people within governments themselves that have not heard of norms too. She mentioned the example of Switzerland: when establishing its national cybersecurity strategy, it has been extremely useful in bringing different actors together to learn about each other’s work. So the same is needed at the inter-state level for building capacities and for implementing norms.

Jan Lemnitzer, Cybersecurity policy expert and lecturer at the Department of Digitalization, Copenhagen Business School, and Vladimir Radunovic, Director of E-Diplomacy and Cybersecurity at DiploFoundation, posed additional questions on how the response would be if a state does not have capacities to respond to an assistance request (norm H) and on how interaction between the public and private sector and security/tech communities should look.

Addressing them, Neil said in both cases that the response would depend on the scale and complexity of the attack. When states don’t have capabilities to address a cyber incident or provide assistance, at least they can share what technical information, attack vectors, some ideas of evidence and intelligence they might have. Hence, transparency and the ability to communicate becomes critical, and all types of response would therefore largely depend on relationships among states. Nadine added that cross-border cooperation is critical, but it concerns not only governments but private sector too. Speaking of norm H and the ‘due diligence’ principle, states need to do what is reasonably feasible for those states; i.e., if they don’t have the capacity they should reach out to other states, and Switzerland, particularly, has had cases when it helped other countries deal with cyber attacks. Bilateral mechanisms are important, but also the global community has other mechanisms of capacity building, e.g., the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise (GFCE), the World Bank’s efforts, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Organization of American States (OAS), and ASEAN.

To all these thoughts, Stefan provided his third-party opinion and agreed that info sharing is important, but that states are not always willing to provide assistance to other states. He particularly mentioned the case of how the FBI assisted the Reykjavik Metropolitan police in their investigation of Silkroad - the first big dark web market -, while European law enforcement agencies showed the Icelandic police the cold shoulder. And how NATO has stood up Rapid Reaction Teams since 2011, to support alliance members in the mitigation and triaging of cyber incidents affecting their military networks. However, what is missing in the current conversation, as Stefan stressed, is the build-up of deployable national capabilities that can be offered to third states under the umbrella of investigative support, humanitarian aid, or even peacekeeping. Furthermore, Stefan noted that governments should ask themselves whether the due diligence principle and state sovereignty should apply to bulletproof hosting servers or whether they should be considered a free game? Stefan noted that in the context of Europol's takedown of Emotet, two of the three C2 nodes were most likely hosted by bulletproof hosters. Similarly, the offensive cyber operation that the Australian Signals Directorate ran against foreign criminal infrastructure in April 2020, was most likely also directed against servers at a bulletproof hoster.

When it comes to cooperation among CERTs, Serge Droz, Chair of FIRST, joined the discussion and said that there is indeed good experience of cooperation among technical specialists and the private sector. The problem arises when politics and policy comes in: particularly, Serge mentioned that they are not allowed to exchange technical information with some companies in China. However, while the policy of a particular state might be wrong, it does not mean that we need to allow vulnerabilities to be exploited by malicious actors.

What are the priorities for further work?

Ivan said that his personal priority is to increase the cost of attacks as much as possible (for attackers obviously). Neil agreed with that and added that we need greater capacity building and greater investments for cybercrime investigations. Nadine supported both points, and added that there is still a lot of work to do to achieve better geopolitics: discussions in the UN are very polarized, but hopefully 2021 will be better in terms of communication among countries.

Blitz poll!

As the main purpose is to learn from each other, we also asked the experts three quick ‘blitz poll’ questions:

- The key event/process the community needs to follow in 2021?

While Neil and Stefan agreed that there are many processes in practice to follow, Nadine mentioned in particular the cyber processes within the UN First Committee, and Ivan mentioned the OFAC’s statement that ransomware payments may be in violation of international sanctions. - What to read/check for learning more about cyber diplomacy?

DiploFoundation’s resources and UNIDIR Cyber Portal are #1 on Nadine’s list; Ivan shared that he prefers anything from Cory Doctorow, Bruce Schneier and Edward Snowden; Stefan invited everyone to visit the upcoming conference on cyber sanctions; while Neil advised to keep up with what’s going on in twitter. - Who do you call if you’re under a cyberattack?

Nadine said that the new national Swiss Center for Cybersecurity would be the first in the contact list; Neil was honest that his spouse would be the first he’d reach out to; while Stefan, as most of attendees, would call a cybersecurity vendor such as Kaspersky; and Ivan would definitely call Costin Raiu first.

Stay tuned for the next Community Talks on Cyber Diplomacy! You can also re-watch the session here: https://kas.pr/k416

[1] Those non-binding norms, as adopted by the UN GGE in 2015, are: (1) ‘States should take appropriate measures to protect their critical infrastructure from ICT threats, taking into account General Assembly resolution 58/199 on the creation of a global culture of cybersecurity and the protection of critical information infrastructures, and other relevant resolutions’ (norm G), and (2) ‘States should respond to appropriate requests for assistance by another State whose critical infrastructure is subject to malicious ICT acts. States should also respond to appropriate requests to mitigate malicious ICT activity aimed at the critical infrastructure of another State emanating from their territory, taking into account due regard for sovereignty’ (norm H).