Stuxnet has become synonymous with cyberattacks and cyberwarfare. To this day, questions continue about who created Stuxnet, how did Stuxnet work, and why Stuxnet is significant to cybersecurity. Read on to find answers to these questions and more.

What is Stuxnet?

Stuxnet is a highly sophisticated computer worm that became widely known in 2010. It exploited previously-unknown Windows zero-day vulnerabilities to infect target systems and spread to other systems. Stuxnet was mainly targeted at the centrifuges of Iran’s uranium enrichment facilities, with the intention of covertly derailing Iran’s then-emerging nuclear program. However, Stuxnet was modified over time to enable it to target other infrastructure such as gas pipes, power plants, and water treatment plants.

Whilst Stuxnet made global headlines in 2010, it’s believed that development on it began in 2005. It is considered the world’s first cyber weapon and for that reason, generated significant media attention. Reportedly, the worm destroyed almost one-fifth of Iran’s nuclear centrifuges, infected over 200,000 computers, and caused 1,000 machines to physically degrade.

How did Stuxnet work?

Stuxnet is highly complex malware, which was carefully designed to affect specific targets only and to cause minimum damage to other devices.

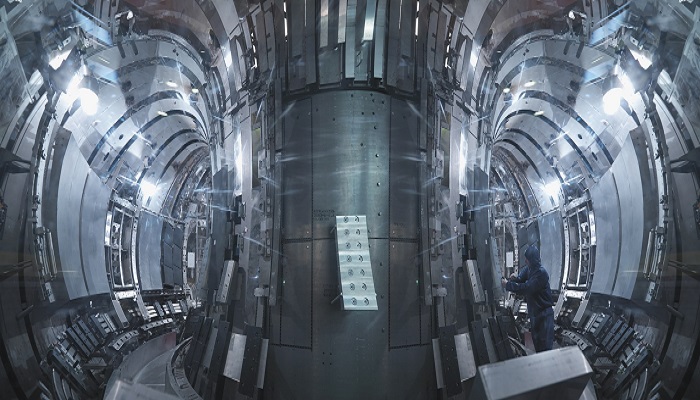

In the early 2000s, Iran was widely thought to be developing nuclear weapons at its uranium enrichment facility at Natanz. Iran’s nuclear facilities were air-gapped – which means they deliberately weren’t connected to other networks or the internet. (The term ‘air gap’ refers to the physical space between an organization’s physical assets and the outside world.) It’s thought that Stuxnet was transmitted via USB sticks carried inside these nuclear facilities by agents.

Stuxnet searched each infected PC for signs of Siemens Step 7 software, which industrial computers serving as programmable logic controllers (PLCs) use to automate and monitor electro-magnetic equipment. Once Stuxnet found this software, it began updating its code to send destructive instructions to the electro-magnetic equipment controlled by the PC. At the same time, Stuxnet sent false feedback to the main controller – which meant anyone monitoring the equipment would not realize anything was amiss until the equipment started to self-destruct.

In essence: Stuxnet manipulated the valves that pumped uranium gas into centrifuges in the reactors at Natanz. It sped up the gas volume and overloaded the spinning centrifuges, causing them to overheat and self-destruct. But to the Iranian scientists watching the computer screens, everything appeared normal.

Stuxnet was highly sophisticated – it used four separate zero-day attacks to infiltrate systems and was designed only to inflict damage on Siemens industrial control systems. Stuxnet comprised three parts:

- A worm that conducted most of the work

- A link file which automated execution of propagated worm copies

- A rootkit which hid files from detection

Stuxnet came to light in 2010 after inspectors at Iran’s nuclear facilities expressed surprise at the rate in which centrifuges were failing. Further investigation by security experts revealed that powerful malicious software was the cause. (One of the security experts was Sergey Ulasen, who subsequently went on to work for Kaspersky.) Stuxnet was difficult to detect because it was a completely new malware with no known signatures, which exploited multiple zero-day vulnerabilities.

Stuxnet was not intended to spread beyond Iran’s nuclear facilities. However, the malware did end up on internet-connected computers and began to spread because of its extremely sophisticated and aggressive nature. However, it did little damage to outside computers it infected – because Stuxnet was designed specifically to damage only certain targets. The impact of Stuxnet was mostly felt in Iran.

Who created Stuxnet?

Whilst no-one officially claimed responsibility for Stuxnet, it is widely accepted that it was a joint creation between the intelligence agencies of the US and Israel. Reportedly, the classified program to develop the worm was code-named ‘Olympic Games’ which began under President George W Bush and then continued under President Obama. The program’s objective was to derail or at least delay Iran’s emerging nuclear program.

Initially, agents planted the Stuxnet malware in four engineering firms associated with Natanz – a key location in Iran for its nuclear program – relying on careless use of USB thumb drives to transport the attack within the facility.

Why is Stuxnet so famous?

Stuxnet generated extensive media interest and was the subject of documentaries and books. To this day, it remains one of the most advanced malware attacks in history. Stuxnet was significant for a number of reasons:

- It was the world’s first digital weapon. Rather than just hijacking targeted computers or stealing information from them, Stuxnet escaped the digital realm to wreak physical destruction on equipment the computers controlled. It set a precedent that attacking another country’s infrastructure through malware was possible.

- It was created at nation state level, and while Stuxnet was not the first cyberwar attack in history, it was considered the most sophisticated at the time.

- It was highly effective: Stuxnet reportedly ruined almost one-fifth of Iran's nuclear centrifuges. Targeting industrial control systems, the worm infected over 200,000 computers and caused 1,000 machines to physically degrade.

- It used four different zero-day vulnerabilities to spread, which was very unusual in 2010 and is still uncommon today. Among those exploits was one so dangerous that it simply required having an icon visible on the screen – no interaction was necessary.

- Stuxnet highlighted the fact that air-gapped networks can be breached – in this case, via infected USB drives. Once Stuxnet was on a system, it spread rapidly, searching out computers with control over Siemens software and PLCs.

Is Stuxnet a virus?

Stuxnet is often referred to as a virus but in fact, it is a computer worm. Although viruses and worms are both types of malware, worms are more sophisticated because they don’t require human interaction to activate – instead, they can self-propagate once they have entered a system.

Besides deleting data, a computer worm can overload networks, consume bandwidth, open a backdoor, diminish hard drive space, and deliver other dangerous malware like rootkits, spyware, and ransomware.

You can read more about the difference between viruses and worm in our article here.

Stuxnet’s legacy

Because of its notoriety, Stuxnet has entered the public consciousness. Alex Gibney, an Oscar-nominated documentarian, directed Zero Days, a 2016 documentary which told the story of Stuxnet and examined its impact on Iran’s relations with the West. Kim Zetter, an award-winning journalist, wrote a book called Countdown to Zero Day, which detailed the discovery and aftermath of Stuxnet. Other books and films have been released too.

The creators of Stuxnet reportedly programmed it to expire in June 2012 and in any case, Siemens issued fixes for its PLC software. However, Stuxnet’s legacy continued in the form of other malware attacks based on the original code. Successors to Stuxnet included:

Duqu (2011)

Duqu was designed to log keystrokes and mine data from industrial facilities, presumably to launch a later attack.

Flame (2012)

Flame was sophisticated spyware that recorded Skype conversations, logged keystrokes, and gathered screenshots, among other activities. Like Stuxnet, Flame traveled via USB stick. It targeted government and educational organizations and some private individuals mostly in Iran and other Middle Eastern countries.

Havex (2013)

Havex’s goal was to gather information from energy, aviation, defense, and pharmaceutical companies, among others. Havex malware targeted mainly US, European, and Canadian organizations.

Industroyer (2016)

This targeted power facilities. It reportedly caused a power outage in Ukraine in December 2016.

Triton (2017)

This targeted the safety systems of a petrochemical plant in the Middle East, raising concerns about the malware creator’s intent to cause physical injury to workers.

Most recent (2018)

An unnamed virus with characteristics of Stuxnet reportedly struck unspecified network infrastructure in Iran in October 2018.

Today, cyber means are widely used for gathering intelligence, sabotage, and information operations by many states and non-state actors, for criminal activities, strategic purposes, or both. However, ordinary computer users have little reason to worry about Stuxnet-based malware attacks, since they are primarily aimed at major industries or infrastructure such as power plants or defense.

Cybersecurity for industrial networks

In the real world, advanced nation state attacks like Stuxnet are rare compared to common, opportunistic disruptions caused by things like ransomware. But Stuxnet highlights the importance of cyber security for any organization. Whether it’s ransomware, computer worms, phishing, business email compromise (BEC), or other cyber threats, steps you can take to protect your organization include:

- Apply a strict Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) policy that prevents employees and contractors from introducing potential threats onto your network.

- Implement a strong and technically-enforced password policy with two-factor authentication that hinders brute force attacks and prevents stolen passwords from becoming threat vectors.

- Secure computers and networks with the latest patches. Keeping up-to-date will ensure you benefit from the latest security fixes.

- Apply easy backup and restore at every level to minimize disruption, especially for critical systems.

- Constantly monitor processors and servers for anomalies.

- Ensure all your devices are protected by comprehensive antivirus. A good antivirus will work 24/7 to protect you against hackers and the latest viruses, ransomware, and spyware.

Related products:

- Kaspersky Antivirus

- Kaspersky Premium Antivirus

- Download Kaspersky Premium Antivirus with 30-Day Free Trial

- Kaspersky Password Manager - Free Trial Version

- Kaspersky VPN Secure Connection

Further reading: